Does a feel-good video of a father teaching his young daughter to dance seem harmful? Most would say “no.” But what if this heartwarming clip came from a social media account that has been accused of taking part in an influence campaign orchestrated by the Russian government, using the video to improve its social algorithm and fund its initiatives?

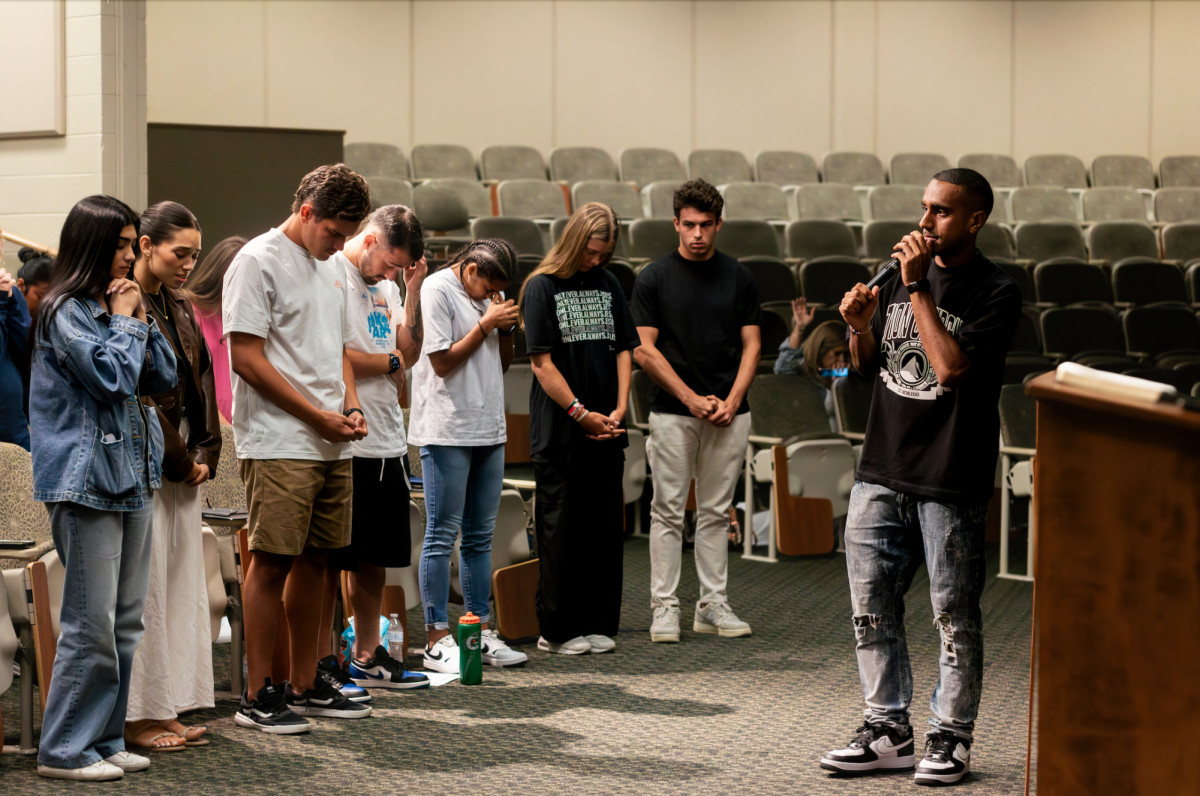

This specific example was introduced by Hannah Covington, a 2014 ORU alumna and senior director of education content at The News Literacy Project, a nonprofit group based Washington, D.C. Covington was on campus recently to meet with ORU media students as part of a Media Literacy workshop in the Digital Society course.

“We live in an age of information abundance,” Covington said. It’s a state of “information overload,” leading to “more confusion than knowledge when it comes to a particular topic.”

Covington discussed the importance of understanding key terms—misinformation and disinformation. Misinformation is false information spread non-maliciously, while disinformation is false but spread knowingly, typically with an agenda.

There are a wide variety of motivations which influence people to spread misinformation. Covington said that some groups may spread misinformation for “financial gain.” Others will spread misinformation for “influence” or to create “political division” and “undermine trust.”

Covington also warned misinformation relies on an “emotional response.” These are often tied to an “intense emotional reaction” which “overrides a rational thought.”

Misinformation uses these emotional responses to influence mass numbers of voters and undermine the democratic process.

“Think about your most deeply held beliefs – those are where you are most vulnerable to manipulation,” Covington said.

Pernell Sterling, a ministry and leadership freshman and social media enthusiast, said that he has fallen victim to “emotional manipulation,” causing him to “sympathize or relate to certain political groups and people.”

David Briggs, a psychology freshman, believes social media plays a part in the spreading of misinformation among students.

“As soon as someone says one thing, social media takes it and runs with it, and whatever misinformation is multiplied as it passes – like a game of telephone from one person to another through social media,” Briggs said.

A recent Oracle student survey confirmed Briggs’ point. Of 258 students responding, 38% said they got their news from social media. Of these, 128 students – about half of the survey takers – admitted to relying on social media for news on the presidential election. Only 26% said that they actively seek out the news once a week.

Covington warned that one of the most recent challenges to the spread of misinformation and disinformation is AI-generated images.

“When you’re scrolling, it is very important to distinguish between high-quality sources and low-quality content,” Covington said.

“Sometimes, when I’m scrolling social media, I’ll see a photo that’s very clearly AI. And I will see hundreds of comments from people who don’t even realize it is AI-generated,” Briggs said.

To combat this, Covington suggested that students fact-check information by using tools such as FactCheck.org, Google Reverse Image Search, and Snopes.com. Also, The News Literacy Project offers Rumor Guard, a web portal debunking recent political election social media posts and election claims.

For more information, check out News Literacy Project or RumorGuard.